Instagram is betting on the momentum, not the reaction

My response to Adam Mosseri.

Last week, Adam Mosseri, Head of Instagram, shared a 2,000-word essay in a post on Threads, on the future of Instagram. In it, he essentially argues that “everything that made creators matter—the ability to be real, to connect, to have a voice that couldn’t be faked—is now suddenly accessible to anyone with the right tools.” He goes on to say that “authenticity” is fast becoming a scarce resource due to AI, which will “in turn drive more demand for creator content, not less.”

Mosseri then makes it crystal clear what kind of creator content he thinks will succeed in this new environment. “The camera companies are betting on the wrong aesthetic. They’re competing to make everyone look like a professional photographer from the past.” He claims that “flattering imagery is cheap to produce and boring to consume. People want content that feels real.” With this, he expects we are going to see a “significant acceleration of a more raw aesthetic over the next few years.” Of course, this is all coming from the guy who posts weekly Reels that are likely shot on a professional camera.

The problem here is that Mosseri is betting on the momentum, not the reaction.

The momentum

This past year, there was a universal “wow, AI is getting too good” moment. It was an image of a woman sitting in a cafe, made using Google’s Nano Banana Pro. It wasn’t because the photo looked professional that made it “realistic”, it was because it looked like a typical photo shot on an iPhone. It had that “raw aesthetic.”

Meanwhile, the company Arcads touts their “AI UGC generator” using “the most realistic and captivating AI Actors” to make videos about your brand’s product. When you scroll through the company’s example videos, they look almost identical to how a real creator shows up on social platforms. The GRWM-ification of AI is already here. Instagram users like Professor EP and Professor EVS create AI influencers. Between the two of them, their accounts, like @isabellasofiarossi and @majafitness, have a cumulative 2.2M followers. Professor EP wrote in a post “AI Influencers are going to be everywhere. This is one of the biggest opportunities of our time — one that will completely transform the multi-billion-dollar social media industry in the coming years.” Commenters often can’t tell that they are AI generated.

In Mosseri’s essay he says, “In a world where everything can be perfected, imperfection becomes a signal. Rawness isn’t just aesthetic preference anymore—it’s proof.”

If Mosseri thinks “rawness” is proof, he’s missing the bigger picture. “Rawness” is now just part of the prompt.

The visual cues that Mosseri is essentially demanding from creators to keep up with AI are the exact same ones AI creators will use first to “appear” more “real.” The TikTok account @loganreed515, which AI literacy creator Jeremy Carrasco revealed is an AI-generated scam, is proof of this. Just watch this video with 11M views.

In the past few weeks, we’ve watched everyone from tech CEOs to The New York Times journalists grapple with how “real” AI is getting. A screenshot of an AI-generated Reddit post went viral and the CEO of DoorDash responded as if it were real. (Casey Newton’s investigation into it on Platformer is worth a read.) The New York Times published an entire article explaining why they couldn’t verify multiple photos of Maduro. Mosseri acknowledges this is happening too, writing that “all the major platforms will do good work identifying AI content, but they will get worse at it over time as AI gets better at imitating reality.” Audiences might hate AI slop, but they hate being tricked by AI more.

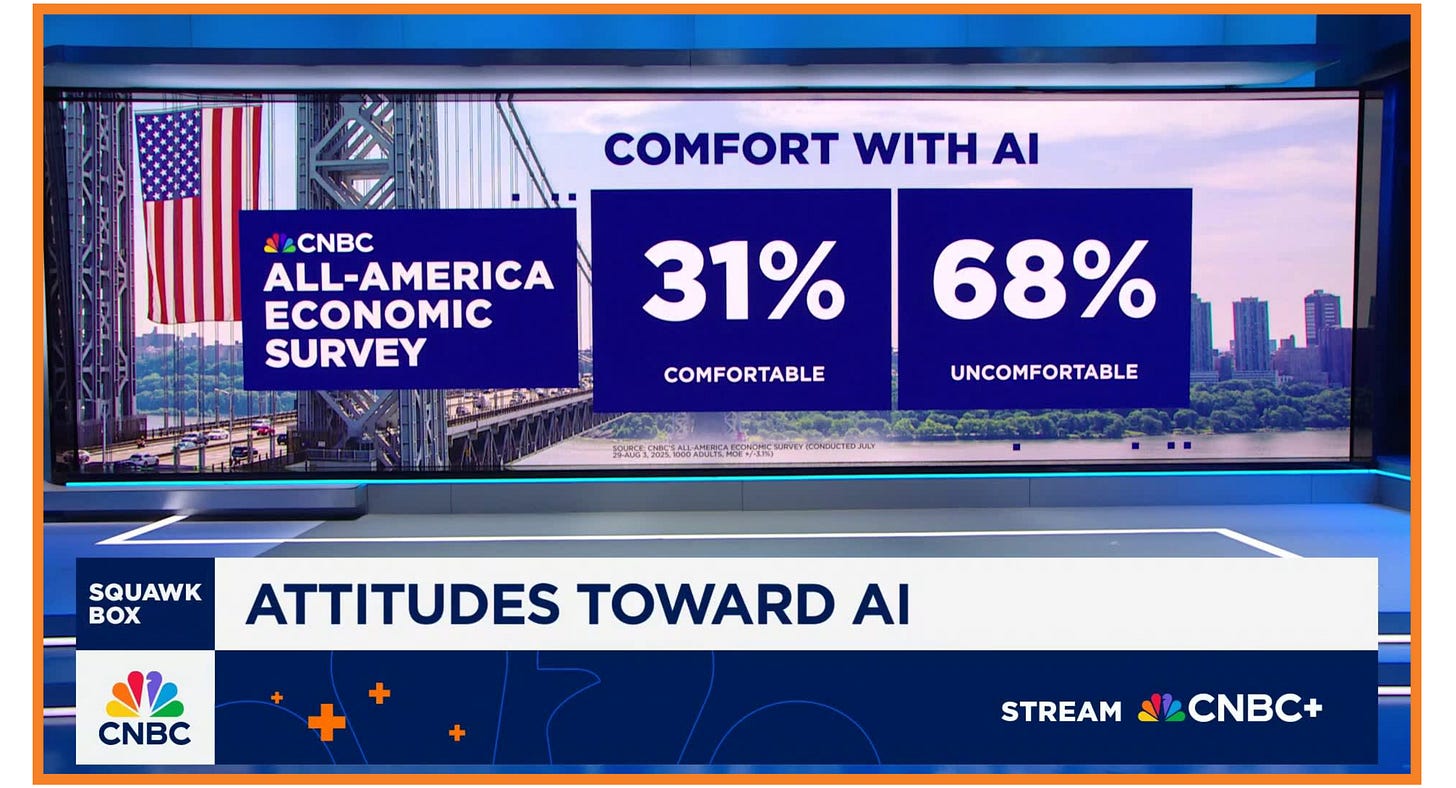

In Greg Ip’s article in The Wall Street Journal, he writes, “While Wall Street greets AI with open arms, ordinary Americans respond with ambivalence, anxiety, even dread.” He goes on to say, “This isn’t like the dot-com era. A survey in 1995 found 72% of respondents comfortable with new technology such as computers and the internet. Just 24% were not. Fast forward to AI now, and those proportions have flipped: just 31% are comfortable with AI while 68% are uncomfortable, a summer survey for CNBC found.” He also included data from a poll of roughly 2,000 people by Narrative Strategies which found just 40% said the AI industry could be “trusted to do the right thing.”

As kyla scanlon succinctly put it in her essay Everyone is Gambling and No One is Happy: “We have all this technology. But we don’t trust each other and we feel terrible.”

The reaction

Let’s leave the camera companies out of it, and focus on the concept of effort. Mosseri wrote, “Savvy creators are going to lean into explicitly unproduced and unflattering images of themselves. In a world where everything can be perfected, imperfection becomes a signal.” I see the opposite being true. As AI-generated content gets more realistic, we’ll see creators lean into craft as a differentiator. It doesn’t matter that you’re shooting on a Sony FX6 or an iPhone 16—it’s about how much work happened before you pressed record. You don’t need a big budget, you need a big idea.

In 2025, we saw creators like Paige Lorenze team up with artists like RJ Bruni to make short films. Skylar Marshai’s creative videos have caught the attention of brands like Microsoft 365 and New Balance. Mayor Zohran Mamdani, one of the politicians most praised for their social media strategy, color graded his Reels like a movie. Comedians like Max Zavidow shot David Lynch-ian Reels that, as I learned in this interview, can take up to six weeks to make. Creators that gained popularity off that “raw aesthetic” are starting to produce more high-effort videos, like Ballerina Farm’s move into a cinematic style. I know Mosseri was speaking to creators specifically in his essay, but I also think about how brands like Ffern and restaurants like Osteria Renata have built dedicated followings from publishing content that inspires comments like “now THIS is art”.

Of course, iPhone footage will always visually feel at home on Instagram, but as AI companies use that as the blueprint for assimilation, then what happens?

Mosseri might be betting on this reaction too, even if he doesn’t know it. In 2025, Instagram created an award called Rings to highlight “the creators who don’t just participate in culture - but shift it, break through whatever barrier holds them back to realize their ambitions.” I went through all 25 of the winners. Around half of them shoot on a professional camera and create what I would deem more polished content. Funny enough, one of the winners, Adrian Per, has gained massive popularity for teaching people how to make cinematic videos.

The distraction

Maybe I’m focusing on the camera portion of Mosseri’s essay too much. But I think that was his goal. Instead of making AI the problem in need of a solution, Mosseri deliberately pointed the blame at the camera companies. It’s on them to “cryptographically sign images at capture, creating a chain of custody.” Flattering imagery is “boring to consume.” In fact, AI might be a good thing because it’ll “drive more demand for creator content, not less.” Coming from the head of a platform that is pushing AI features and clearly profiting off of AI content, this all feels a bit disingenuous.

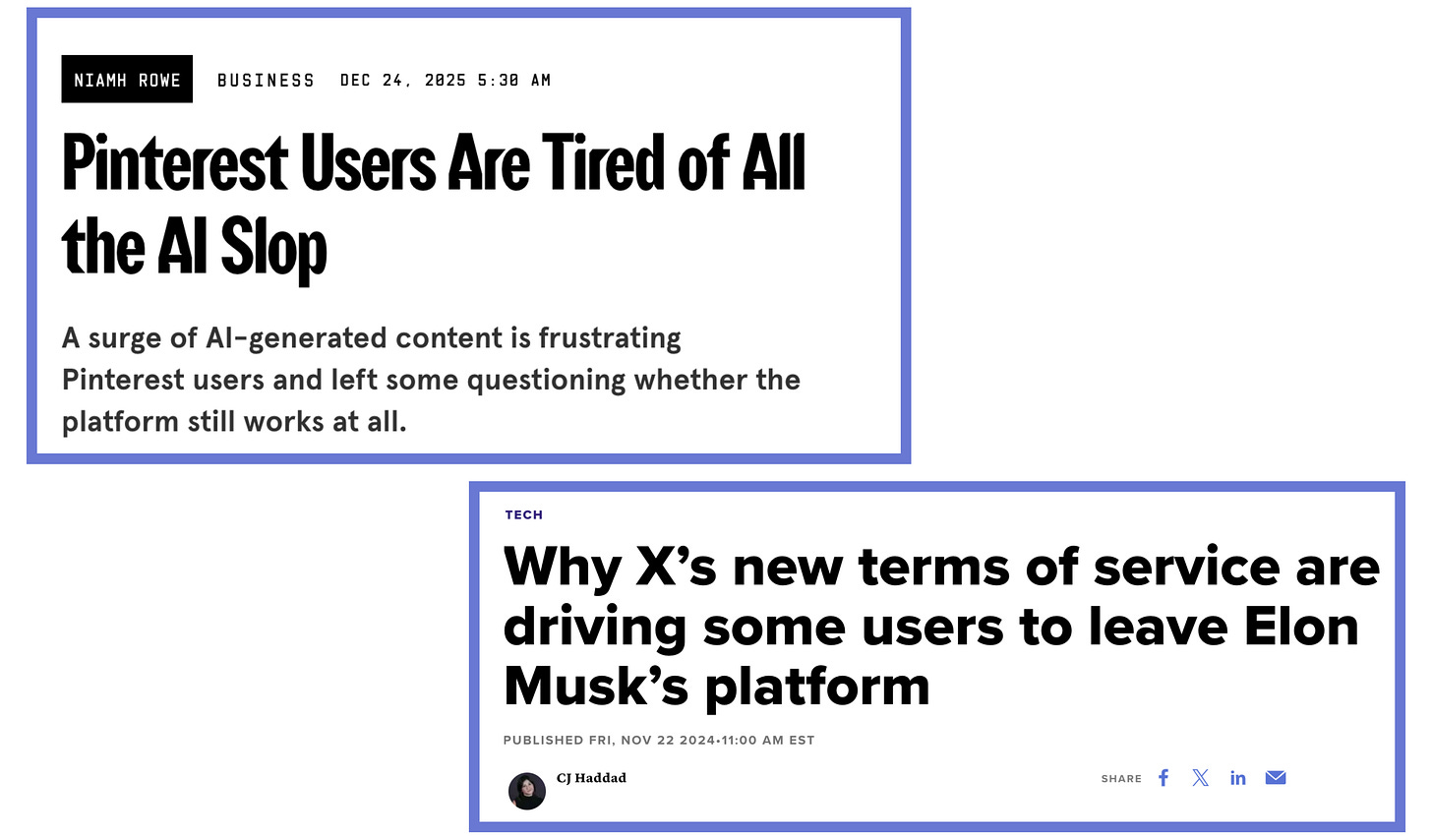

I write this response because I care about Instagram. I’ve worked in social media for over 12 years and in that time have seen the positive impact the platform has had on creators and businesses. I’ve built my career around it. To me, the biggest threat to users on Instagram isn’t about aesthetics, it’s about AI. It’s about skepticism getting so loud that even creator posts are drowned in comments like “is this AI?” It’s about the experience of scrolling feeling worse—with regrettable minutes adding up. We’ve already seen this happening on Pinterest and X. A new study from Kapwing found that “21-33% of YouTube’s feed may consist of AI slop or brainrot videos.” In my opinion, the danger to creators isn’t that they aren’t posting enough blurry photos, the danger is a continuing slow creep of AI content leading to their followers using Instagram less, or even leaving Instagram entirely.

Mosseri does propose a few solutions—like labeling AI-generated content, surfacing “credibility signals” about accounts, and building “the best creative tools, AI-driven and traditional, for creators so that they can compete with content fully created by AI.” Instead of expanding on how they plan to get any of this done, these proposed solves unfortunately end up feeling like passive afterthoughts. Mosseri ends the essay talking about the need to improve ranking for originality, but “tackling algorithmic transparency and control is probably best left for another essay.” There’s always tomorrow.

If Mosseri were being honest with himself on how to keep Instagram “authentic”, he would have used his essay to advocate for AI regulation, creator protections, and industry standards. To introduce a program that shields creators from AI copycats trained off their likeness and their posts. To take his own advice and lean into “unflattering” content. Being truthful about the problem AI poses to Instagram creators won’t always make you look good, but at least it will be “authentic”.

If you enjoy free essays like this one, you can upgrade to a paid Link in Bio subscription. You’ll get weekly strategy newsletters and quarterly trend reports, along with access to the Discord community.

It might even be an educational expense at your company! Here’s a template for you to use when asking.

And if you’re already a paid subscriber, ignore this and thank you!

Typical tech leaders talking out of both sides of their mouths, trying to have their cake and eat it too. Facebook used to call itself a media company, until it decimated print journalism and started genocides. Then it's "we're just a tech company." They're willing to take AI dollars now, but when social media collapses from slop, they'll blame creators.

God, I miss when the internet was fun.

I agree that AI is flattening aesthetics, but I’m less convinced that “rawness” (aka forced authenticity) is the antidote. As AI gets better at mimicking imperfection, the iPhone look, the GRWM style, even awkward framing quickly become part of the prompt. A blurry photo doesn’t prove humanity any more than a color grade disproves it.

What still feels scarce isn’t rawness, but intention, message, content, point of view, judgment, and the thinking that happens before the camera turns on. If platforms want authenticity, the real work isn’t aesthetic, it’s structural: trust, transparency, and meaningful protections for original creators. Otherwise skepticism fills the gap, and even genuinely human content gets questioned.